Photo by Bex Wade

Nick Mason: Sound Investments

Words by Tom Hoare

“Nick doesn’t tend to do interviews.” My heart sank as I read the email. Resisting the urge to swear loudly, I rationalised that when you’re the drummer of one of the most commercially successful and musically influential bands of all time, you don’t really need to do them.

Perhaps I’d been somewhat presumptuous. The book I’d been reading only five minutes previous is entitled Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd. Written by Nick himself, it details the highs and lows of the band’s career; from recording some of the most iconic albums in popular music history to the animosity which led to the band’s demise.

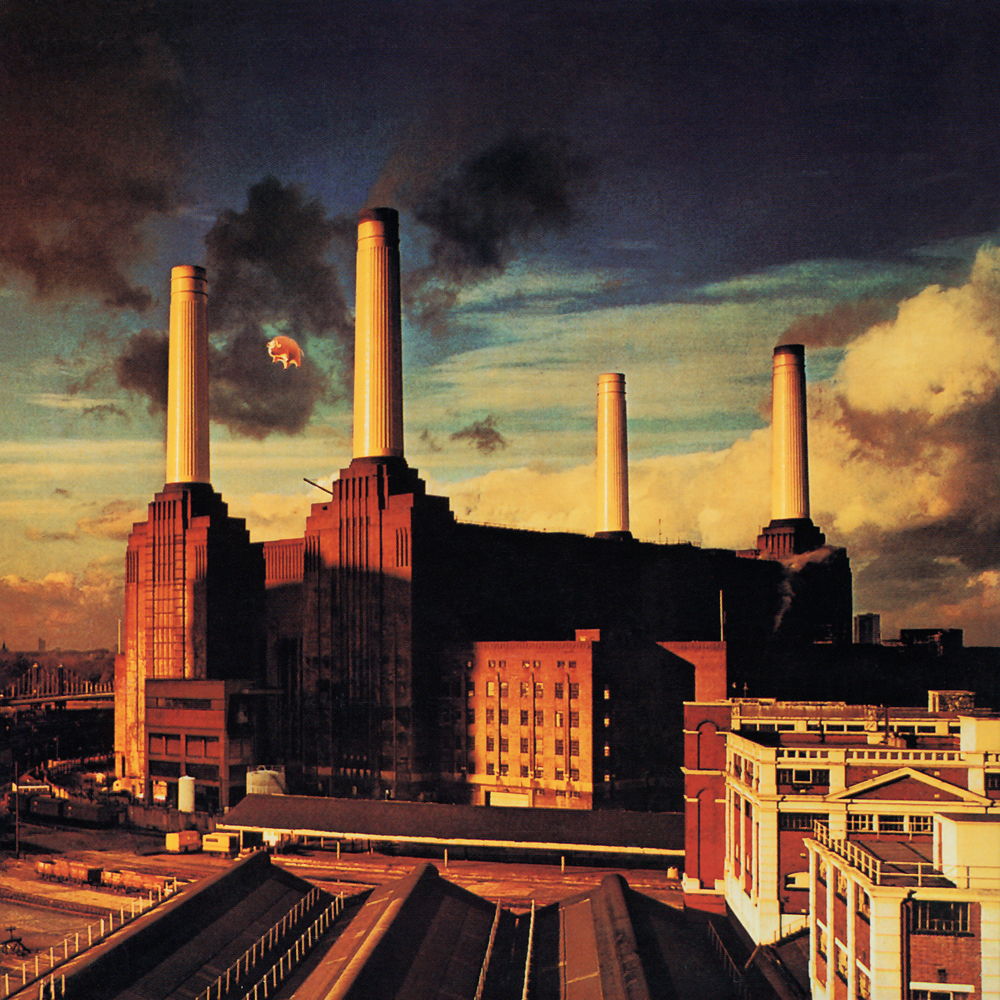

The book’s cover displays the graphic of a pig hovering above Battersea Power Station. This image is a derivative of the artwork for Pink Floyd’s 1977 album, Animals. To capture the original still, a giant inflatable pig was tethered to one of the power station’s chimneys. The pig then broke free from its moorings and drifted into the flight path of planes on approach to Heathrow airport, much to the surprise of the pilots no doubt. It eventually landed in a field in Kent where an upset farmer claimed it had, “scared the cows.”

The email concluded: “Let me get back to you. It may be a while.” Even though pigs have apparently flown previously for Pink Floyd, I felt this likely wouldn’t be such an occasion.

Several months later I’m stood outside a private members club in west London, conscious that my scuffed trainers stand somewhat at odds with the three piece suits that are entering and exiting the building. Acutely aware of looking like a vagrant, I attempt a stealthy shuffle to the elevator to avoid attracting the attentions of those behind the reception desk.

“Can I help you?”

In what was originally an effort to avoid arousing suspicion, I’m now stood frozen in motion about a metre away from the elevator. Making things more awkward, my response is delivered in the form of a question: “I’m here to see Nick Mason?”

“Floor Three.”

The elevator doors open, revealing a busy room with large glass windows and lots of sofas. Beyond the business lunches, the chimneys of Battersea Power Station are visible in the distance.

I’m directed to an armchair opposite two men talking about fiscal regulation. Feeling particularly imposturous, I try and obscure myself behind a broad, pink newspaper. It also serves to cover the large penguin on the front of my jumper, which I’m confident doesn’t pass as business casual.

Nick arrives with one hand outstretched and a host of papers clutched in the other. Seemingly unfazed by the penguin, he smiles and gestures down the corridor. “We’re in Conference Room B, I’ll be with you in a minute.”

This building is partly owned by Nick. Following Pink Floyd’s decision to disband, he was able to indulge other interests in motorsport and aviation. He also has a significant investment portfolio, which includes the famous London musical institution, Foote’s Music. I was pleased to hear this. Nick had stepped in and, in part, helped the shop avoid closure after almost a century of trading.

In Conference Room B, Nick is sat before a rather imposing stack of papers, glancing fleetingly at his watch. Best begin.

Photo by Bex Wade

The Drummer’s Journal: You got your first kit from Foote’s Music and now you’ve become a shareholder in the shop...

Nick Mason: Foote’s has existed since 1920. When I heard the shop was to close because of problems with the bank, I felt it was such a shame to lose a place like that. I called the owners and said I’d consider putting some money in because I’ve always felt drum shops are lovely places.

Was it more of a personal investment as opposed to a financial one?

In some ways, yes. I don’t see an enormous profit in it, but I think it could be successful. That said, I didn’t buy a music shop as a vanity project. I just like drum shops and I like people who go into drum shops (laughs).

Seeing Ginger Baker play made quite an impression on you. How would you describe the evolution of drumming in the 1960s?

Prior to 1960, drummers for pop groups were on a riser at the back with someone good looking at the front nodding along to the music. With Ginger, it suddenly became about a band and not just about a pop star and that was enormously attractive to a lot of people. It challenged the idea that popular music was for teenage girls. For Cream, the reality was that the main audience were all guys in trench coats (laughs).

When I look back at the 1960s, it seems like the decade of the superstar drummer - John Bonham, Keith Moon, Ginger Baker and Ringo Starr. Would you agree?

Yes and no. There was a period of superstar drummers before them; Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa and Louis Bellson - the big band swing drummers - they did stick tricks and had double bass drums too.

And this projected on what you wanted to be as a musician?

Yes. Absolutely. I wanted to be part of it, not behind it.

You said initially that you didn’t feel technically proficient as a player…

Yes. I still feel that. I’m still learning to live with it.

Did that make you self-conscious as a musician?

It still does. It’s hard to know now but if I’d had lessons there’s an argument to say that I wouldn’t have played the way I did. The upside is I’m grateful to have developed my own style.

You spent time travelling around the USA in the 1960s. You met a newly-wed couple on a Greyhound bus, where the husband stated he was leaving the week after to serve in Vietnam. For me, the 1960s seems like a really polarised decade - there’s a lot of romanticism about it, when in actual fact it wasn’t all peace and love…

Yeah, absolutely. In America it was a lot grittier because they were fighting a war. I think it was very short lived, the whole Summer of Love because it became commercial almost instantly. The period of free concerts and all the rest of it was very brief before it became, “hang on, this band could sell a million albums.”

Do you feel that music does have revolutionary potential?

I think it’s overrated but there is an element there. Its ability to change perceptions is limited - it actually becomes quite partisan. People often identify themselves by the music they like. In the 1960s, if people were into certain bands it was usually a good indication as to what their politics were, where they were educated and even their social class. But sometimes, with someone like Bob Dylan, there are people who can send messages of considerable importance.

Would you consider yourself someone like that?

No.

Photo by Bex Wade

With Pink Floyd there was no sugar-coating the commercial aspirations of the band…

Right. What was blindingly obvious pretty early on was that if you were successful you could have more studio time, bigger shows, better equipment and better sound.

With some of your early shows, the press made a big deal out of the LSD association and freak-out aspects. Did you actually feel subversive?

No. We were never that mad about being called psychedelic, that was a very brief period. Saying that, music is whatever you believe it to be and if people wanted to take LSD and trip to our music so be it, but it wasn’t written in that way.

You described the transition from architecture student to professional musician as, “being propelled into a position of fantasy.” Did you feel yourself changing as a person throughout that process?

I’d say it’s actually quite rare for people to feel they change as a person. People often ask what it was like and I always say it was just normal - we just got on with what we were doing. It wasn’t like we suddenly had gold plated taps. The transition from being a student to being in the back of van wasn’t that shocking.

The Dark Side of the Moon is one of the most famous albums in the world…

I couldn’t possibly comment (laughs).

If you were to present someone with an album which you felt encapsulated what you wanted to achieve as a musician, what would you choose?

I’d choose Dark Side. It’s the most complete album. There’re lots of others I like, but Dark Side has a lovely mix of everyone contributing to it. I think The Wall was a hell of a piece of work but it’s probably too long. What might have been nice to have Dark Side a little longer and The Wall a little shorter. It’s got some great songs, and Roger’s lyrics are extraordinary. The fact he was only 23 still amazes me. A question I get asked all the time is, “why is Dark Side so successful?” Apart from the marvellous Rototoms which was obviously the main selling point (laughs), the truth is Capitol Records decided to make this record work - we had total support from the label.

What did you get from your solo material that you couldn’t achieve with Pink Floyd?

Not operating as a group and not having to worry about group acceptance with some quite powerful people is a great release. I think drummers by nature operate in bands, not as solo artists. There’s the old joke that a band is a rhythm section and a couple of novelty acts, but you can’t go on tour solely as a drummer. I think I prefer doing production to solo records really. It was great to have the opportunity but if someone asked if I wanted to do another solo album I’d say, “not really.”

Do you want to do another solo album?

Not really.

When things were becoming more challenging interpersonally in the band, did that ever affect how you saw the drum set as an instrument? Did you ever resent having to play?

Do you mean, did I ever lose the enthusiasm? Well, the answer to that is no. There were odd moments where I became conscious that things might implode. I think it divides up into people who project resentment onto whatever they might be doing, or people who think it’s all ok when they’re playing. The latter was the case for me, even when we were doing The Wall shows and things were getting difficult. Rick [Wright] had been taken out of the band but brought back in for the shows and, yes, relations were very strained. We all had separate portacabins for the shows at Earls Court. But being on stage was always great. And that’s where the interaction was.

To reunite for Live 8 in 2005 - what did that mean to you personally?

I really wanted to establish that we are grown up enough to do things for one another. Also, it was in memory of all the good things that happened. We do have a reputation as being the band that always fought, but I think the reality is that a lot of bands do. Most of the time we spent together was terrific and recognition of that is important. For me personally, it was also important from the point of view of my children - seeing that adults can get together, set aside their differences and do the right thing for the right reason.

How would you describe it as an experience? Playing together again on stage as Pink Floyd after 25 years?

It’s very hard to describe. It was such fun but it was also much more than that. It gave an enormous amount of pleasure, more really, to people who’d been fans for years - the people who have, essentially, paid for all our lifestyles. I know I’ve frittered mine away on old cars, maybe I should have invested it wisely (laughs).

You said what you liked about music was the shared experience of being in a band. Do you feel that translates to motorsport? Motorsport strikes me as being a bit lonely…

The team aspect of motorsport is vaguely similar, but the big thing is that when you are in a car you are totally on your own. The great thing in a band is that when things go wrong you can share it with three or four other people. Certainly the first rule of drumming is that if you make a mistake, turn round and look angrily at the bass player (laughs).

In terms of what you’ve achieved with Pink Floyd and what you’ve achieved in other areas, such as racing Le Mans or writing the book, are they comparable in terms of what they mean as achievements? Do some mean more than others?

Not really because they’re very different. I’d say they compliment each other, but the motorsport thing is more personal. With the band, it’s not just me, I’m part of a group, so however successful that is it’s not my personal success, it’s a collaborative success. The book actually is a better example - it’s mine. When I take credit for it, it’s my book. If someone wants to tell me how utterly wonderful it is, I’m happy to sit there and simper. If someone wants to tell me how great the band is, it’s almost more irritating. Don’t get me wrong, it’s great people like it and I’d far rather people told me that they’re fans of Pink Floyd instead of Deep Purple, but achievements related to the band I almost see as once removed.

With the book, how was the writing process?

I really enjoyed it. The only difficult thing was getting started because of the endless deliberation on whether the book should be done by the band or by an individual. And trying to reach an agreement on any story – it became obvious it wasn’t going to happen. So I thought, well, I’m going to do my own version. You guys can all write your own books.

Was it a self-reflective process as much as reflecting on others?

Yes, very much so. There were bits that were quite painful, dealing with Rick leaving, Roger leaving and all the rest of it. But it’s interesting how many things get forgotten that you have to be reminded of. Also, there were people who were very important to the stories who have died or gone missing. That made me feel it was important to get the thing written.

Now you have an honorary doctorate from the University of Westminster, do people address you as Dr Nick Mason?

No, unfortunately not (laughs). Initially, when it was suggested, I loved the idea but thought the others would sneer at me. Then I found out that David Gilmour had already accepted one from somewhere, so I thought, “stuff that I want one too!

Photo by Bex Wade